The Pioneer of Independent Filmmaking: John Cassavetes

By: Zachary Weber

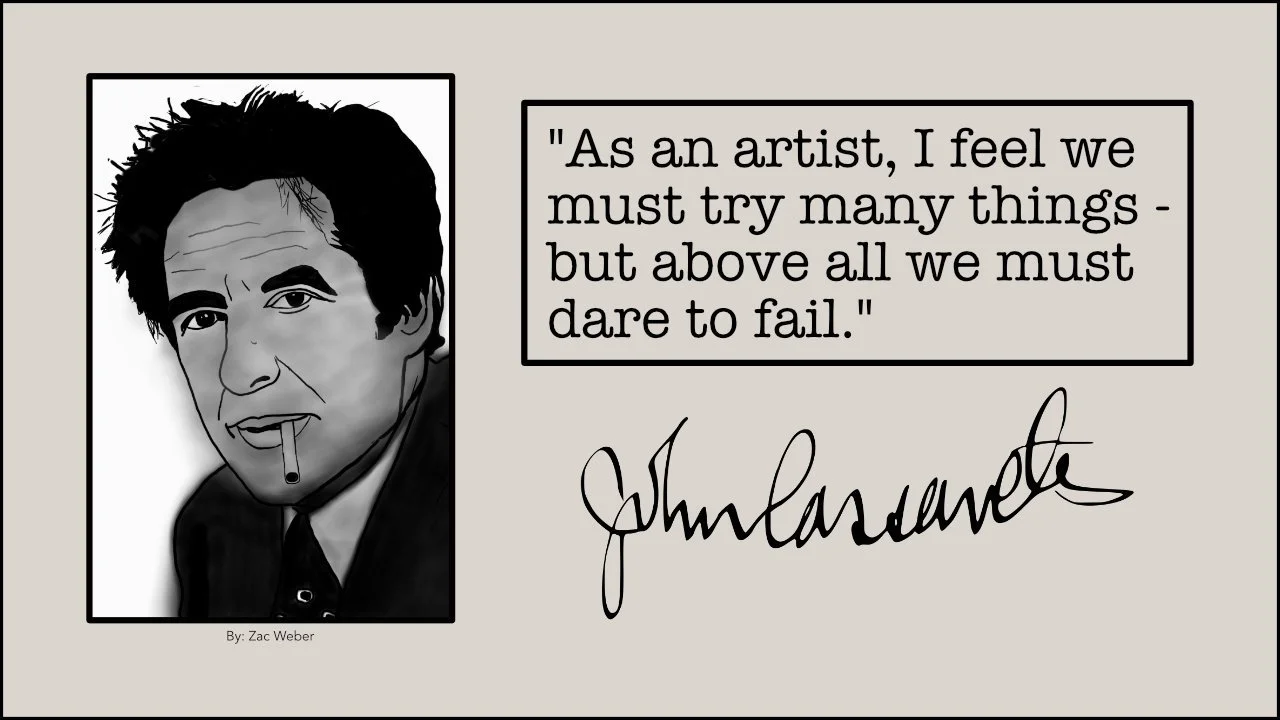

As we patiently wait for solidarity to ensue with the 2023 WGA Writer’s Strike, there couldn’t be a more opportune time to discuss independent filmmaking. I realize it may also be a touchy subject, however, this essay isn’t about independent filmmaking per se. It’s certainly not about the 2023 WGA Writer’s Strike either. It’s about the legendary writer and director, John Cassavetes.

My brother Justin and I have been pursuing a career in filmmaking (of some kind) for the past few years. Living east of Hollywood in the hot Arizona desert, we thought, “Hey, let’s use our equipment and make our own films.” Easy enough, right? Wrong. What we’d failed to realize is not only do you need an army to make a film, you need trucks loads of cash. It’s really sickening when you start to realize how expensive a film is on any scale. It was a heartbreaking day for the broke brothers to realize a “Micro-Shoestring Budget” was any film under $50,000 (even that number is argued) and any halfway decent short film even costs a few grand. Well, there goes the idea of us writing, directing, and producing our own films on our own streaming site for our tiny audience (from our former podcast), all on our own. Lucky for us, there was a better way to do it. It was one doing it long before us, in a much more difficult time. The films were even more expensive to make after you factor the time and money spent, inflation, etc. If that’s not motivating, then nothing is. All we need is equally passionate crew members and good stories to tell.

Early along my journey I found a biography on John Cassavetes titled, Accidental Genius: How John Cassavetes Invented the Independent Film by Marshall Fine. Around this same time, I was trying to understand how independent filmmaking worked. How did I ever come up on John Cassavetes to begin with? Let me digress, it’s semi-strange. As well as film, I love music. A band I’ve loved since I was a kid is the Red Hot Chili Peppers. Being a hobby guitar player, I’m a huge fan of their guitarist, John Frusciante. He’s in my personal top five. Going down a Chili Pepper / Frusciante rabbit hole I found a horrifying interview of John Frusciante at his publicly worst point in life (interview starts at 4:27). For those that are unaware, John struggled severely with drug abuse early in his career. The interview was fascinating to hear and see him in that frame of mind, but I’ll try and stay on track here. Conveniently, an interview with the guy who interviewed John in 1994 (Bram Van Splunteren), appeared in my algorithm, where he talks about that day years later. The interview was brand new and current at the time. It was truly destiny! Moving along, I watched the interview to hear his perspective on the infamous 1994 interview. Thirty-seven minutes in, Bram reminisces on how he talked filmmaking with Frusciante to enhance the comfort before the interview started. At this moment, he recounts how he and Frusciante shared a common interest in the films of John Cassavetes when John said, “I know him! He’s my favorite filmmaker!” I couldn’t click open another tab on my computer any faster. I fervently typed his name to see who he was. As I briefly scrolled, I could overhear Bram recall Cassavetes films as, “raw, documentary-looking, fiction”. He went as far to relate Frusciante’s solo music to Cassavetes’ filmmaking style. This was all I needed to study the works of John Cassavetes. In record time, I found Marshall Fine’s biography, Accidental Genius: How John Cassavetes Invented the Independent Film and had it shipped to my door. To this day, I am forever grateful for the continued artistic inspirations bequeathed by the two John’s. Frusciante and Cassavetes.

Since the book was ordered on Amazon, it arrived almost immediately. I got the paperback, it wasn’t as expensive when I bought it, the hard copy is the less expensive version at this time. Inventory may be shrinking, so get it while you can! Right now, the hardcover is pretty inexpensive. There may also be some used options available.

I was initially shocked with how big it was. It’s almost five hundred pages worth of John’s elaborate career. It dives into John’s start in the film industry, as an actor. For those that have seen John Cassavetes act, it’s the no secret the guy had a raw, authentic, natural ability. He spent the the bulk of his early career acting in a number of TV series. He appeared on about a dozen or so shows before making his first feature film, Shadows (1958). Later, he starred in critically-acclaimed films such as The Dirty Dozen (1967) and Rosemary’s Baby (1968).

Being from New York City, John Cassavetes drafted an idea to film himself right in the heart of the big apple. The film was Shadows (1958), a film that changed the independent filmmaking process, forever. The idea was unique in the sense he put out an ad for a local acting classes, where he’d teach acting to anyone interested. No experience needed. With his amateur students, he thought to make Shadows after a few solid foundational lessons. The film was primarily improvised which created a host of difficulties in the editing process. Unfortunately due the times, Cassavetes took months to edit and ultimately had to recut and reshoot. John was adamant about not making a film like that again. After Shadows gained traction in the cinema space, Cassavetes became known as the “improvising-writer-director”. To this day, he’s labeled as improvisational when it wasn’t necessarily always the case. For Cassavetes, this was a perfect learning experience, not something he necessarily wanted to do again.

Having an extensive acting career, John Cassavetes knew exactly how to cater to the needs of his cast and crew, creating a fun working environment. At that time, the role of a filmmaker was interesting in America. It didn’t really shift in the mainstream industry until the late sixties and early seventies (when John was releasing some of his best work) with the rise of young filmmakers taking inspiration from foreign cinema. Early in America cinema, the role of the director was primarily to manage the set more or less. When you read classic screenplays you find lots of intricate camera movements whereas in the modern screenplay, camera directing is almost forbidden. Many early screenwriters were writers only and the directors were directors only. For John, he spent the majority of his early career in this era of filmmaking. When he was bit by the filmmaking bug, he knew he wanted to do it differently than the rest of industry. In the late fifties and early sixties, the handheld camera took over the tripod in Europe, slightly after Shadows, which unlocked a plethora of creative possibilities. This type of realism and raw cinematography fascinated Cassavetes to the point where he saw no reason why he couldn’t make true, personal films that feel real to the viewers. Again, next time would be much different. To him, Shadows was an experiment.

There is no John Cassavetes with out his incredible support system and wife, Gena Rowlands. They were a perfect pair as Gena is a world-class actor herself. The couple originally met at AADA (America Academy of Dramatic Arts) as acting students. At the time, Gena wanted to focus on her career and knew getting into anything romantic with John could halt that. John Cassavetes however, prevailed. They married in 1954.

Thankfully the adversaries of Shadows didn’t stop him for long, instead, he wrote like a madman and acted in a few television series’. Basically after Shadows, John used his acting as a piggy bank to fund his artistic endeavors, making personal films. He’d continue this routine for the rest of his career, also investing profits from his successful films. But, instead, more fuel was put to the fire as Too Late Blues (1961), was a studio disaster. Too Late Blues was a studio opportunity with Paramount and a headache for Cassavetes from the start. Going into the film he was already convinced the studio system wasn’t for him saying he’d never make films that way and felt you immediately lose all control of the project. He’d learned a bit working in the studio system picking up slack on Johnny Staccato (1959-1960) where he starred and learned a ton behind camera directing a few episodes. Too Late Blues struggled from the jump with its screenplay. It’s been said by numerous people, in varying roles, all agree the script is high up on the priority list. John said, “Later, I realized that I had to fight the studio system, which I did. That’s why Too Late Blues is an incomplete film.” As you could imagine, with the rocky relationship with the studios, made for a shaky end result with the film. The film received mixed reviews upon its release, most critics seemingly favored the negative. It’s safe to safe, after this film, John would steer clear of the making a film like that. John Cassavetes and the studio system is water and oil - it doesn’t mix.

Shortly after, Cassavetes was enlisted to direct a film, A Child Is Waiting (1963) discussing a touching subject matter starring Burt Lancaster where he plays a “tough love" psychologist who heads a boarding school for the developmentally challenged. For this kind of film to be his second studio feature, is quite the risk when you take the subject and time it was released. Those weren’t necessarily the most accepting times as it related to the developmentally challenged members of society. For Cassavetes, it was a challenge he could not only take on, but overcome.

After A Child Is Waiting, there was a bit of a hiatus from John on the directing front. It was a time to regroup, write, and figure out how to pave his own way. By the late sixties John Cassavetes seemed to figure out his workflow. On a side note, the persistence that he had to make his films is unprecedented. There was no stopping the man, he would figure it out at all costs. He’s living proof that success takes patience, persistence, and grit. He never stopped writing, it didn’t matter what rejection came from the industry. It’s been noted that he’d written over forty un-produced screenplays that he didn’t want made when he was gone. I’d love to get my hands on some of those. He was a pure artist and kept consistent with his word. One of my favorite Cassavetes films, Faces (1968), was his next masterpiece where he follows an aging man who leaves his wife for a younger woman. His ex-wife then pursues a romantic relationship with a younger partner of her own. The film was done brilliantly in the sense it feels so true to life, still decades later. I was born decades later, yet this subject is still just as relevant today and easily digestible; equally discomforting at times. He was fully aware of the toxicity and flaws that come with human behavior and a showcased these issues tactfully.

As the seventies came around, Cassavetes wrote and directed Husbands (1970), Minnie and Moskowitz (1972), and A Woman Under the Influence (1974). All three fantastic films touch on the topic of love in some way shape or form. All outside the big studio system. Another skill I admire of John Cassavetes is the confidence to divulge into the human psyche in a non manufactured way. Show the way we truly are, as humans. His ability to be vulnerable but remain a masculine figure without crossing into the “toxic masculinity” territory is unmatched, stepping over any fear of failure. Many male writers struggle writing for female characters, Cassavetes didn’t. He just understood people as a whole that well. Maybe it starts with yourself, he seemed to be grounded and understood himself. Not to mention, it’s impressive to be such a true artist without seeming or actual being pretentious. He did it perfectly. In all his films, he’s able to mesh his personal truths in a non invasive way that feels like you’re looking in. There’s no preaching in his Cassavetes’ films, only opening a continued conversation inside your subconscious, which I argue all art should do.

In the mid to late seventies, he wrote and directed The Killing of a Chinese Bookie (1976), which flopped commercially. I liked the film, it’s not your typical John Cassavetes film in terms of subject, but it still has that John Cassavetes feel. After that, he wrote and directed Opening Night (1977), another spectacular film that dives into human behavior. Gena Rowlands performance in Opening Night is right up there with her (arguably) best performance in A Woman Under the Influence. In Opening Night, Gena Rowlands plays a Broadway actress with an extensive background, who struggles with mental health, self-esteem, and romance. Again, John Cassavetes knew exactly how to tackle these difficult subject matters in a time no one was talking about them. So much to the point it’s still relevant today!

John Cassavetes rounded his career with a couple more great pictures. Gloria (1980) was a film starring his wife, Gena. He wanted to write a film for her and this was his piece. I really enjoyed the film, it was a bit different from the normal Cassavetes, but a great “action/drama”. The film received backing from Columbia, where he eased on the idea of working with a studio but as usual, it wasn’t his favorite. After, in his last “personal” film, Love Streams (1984); a film that follows a middle aged brother and sister who are forced to rely on each other. It’s a film I ashamedly have yet to see (I can’t find it anywhere so I’ll most likely buy the DVD and start a Cassavetes collection). Nonetheless it’s a film I will see and most likely enjoy. In his last directing job, he worked on a film that he didn’t write, Big Trouble (1986). The film was another Columbia gig and the initial screenplay was written by Andrew Bergman. From the start, Cassavetes didn’t like the film. In fact, the entire production was in complete disarray by the time he’d gotten there. “It’s aptly named, that picture”, Cassavetes said on Big Trouble.

Unfortunately, John passed away in 1989 as his long battle with cirrhosis of the liver. Being a heavy drinker throughout his adult life, his health deteriorated at light speed in the eighties, although he was able to kick the habit in his later years. But, none of that is to be taken from the masterful career John’s had as well as the unadulterated wisdom he left behind. His films and career are rightfully marveled and should continue to be.

What mades John Cassavetes’ writing style so unique is how well suited it was for an actor’s creative freedoms. For some actors, it was a blessing and a curse. Some had a very difficult time almost “creating” the character from within themselves rather than taking directly from the page. He felt his job as a writer was to set the stage, create a foundation; the actor then was to creatively make their own decisions as it related to the specifics of the character. Rather than total improvisation, he left more room for interpretation with the characters, allowing the actors to fully explore the character without creating too many limiting boundaries. Once the actors got comfortable with Cassavetes’ directing style, they thoroughly enjoyed working with him and often continued to throughout their careers. They were all friends and family on the sets together. In addition, John would frequently invite friends over for table readings for finished screenplays. By the sounds of it, he was just an all around fun individual.

John Cassavetes was an inspiration and mentor to many. Most notably, he mentored a nervous, young filmmaker arriving to L.A. from New York City. That filmmaker was Martin Scorsese. Shot in his home city, Shadows, made Scorsese a Cassavetes fan for life. When he moved out to Los Angeles he was luckily able to connect with John. In fact, Cassavetes let a young Scorsese sleep at a location and gave him a credit as an assistant sound editor on Minnie and Moskowitz. It could be argued that John gave Scorsese the initial confidence to move forward with Mean Streets (1973), his breakout feature film that was a personal one that takes place in Marty’s home of New York. They were so close that Martin Scorsese was mortified when he found out that Ellen Burstyn edged out Gena Rowlands for 1975’s Best Actress In a Leading Role for her performance in Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore (1974), directed by Scorsese. A Woman Under the Influence, for Rowlands.

His impact on future filmmakers didn’t stop with Martin Scorsese and peers alike. John and Gena furthered cemented their legacy with three children, Nick, Alexandra, and Zoe. All three carried on the Cassavetes legacy in the film industry in some way. His eldest, Nick, directed the film adaptation of The Notebook (2004), John Q (2002), and he also wrote the screenplay for Blow (2001). In addition, prior to passing, John gifted his son, Nick, the screenplay of She’s So Lovely (1997) to direct. In some ways this kicked Nick off as a true filmmaker of his own, having an extensive career following.

More than artistic expression, Cassavetes paved a way for independent filmmaking. He humbly views every film as a learning experience and kept his authentic self at the forefront of his work. Studying his career and work not only shows the to-do but the not-to-do as well, which is mastery at its finest. It’d be pointless to study someone who’s “knocked it out of the park every at bat”. What is there to learn from for the rest of us? For us who might not be the “freak of nature” out there seemingly doing everything perfect? What Cassavetes shows us, is that when you stay true to your honest self and stay on your path, you can’t help but become an Accidental Genius.